Tags

1839, brotherton, Brothertown, Brothertown Historical Documents, Brothertown Indians, brothertown new york, brothertown wisconsin, citizenship, Commuck, eeyamquittoowauconnuck, Eeyawquittoowauconnuck, Fox River, Lake Winnebago, Native American, native american tribes of new york, native american tribes of wisconsin, New York Indians, peacemakers, wisconsin indians

185 years ago today, on March 3, 1839, Congress passed Bill #1112, “For the Relief of the Brothertown Indians, in the Territory of Wisconsin.” What precipitated this bill and what were its consequences? Read on to find out.

The Forced Removal of the Brothertown Indians © 2024 by Brothertown Citizen is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

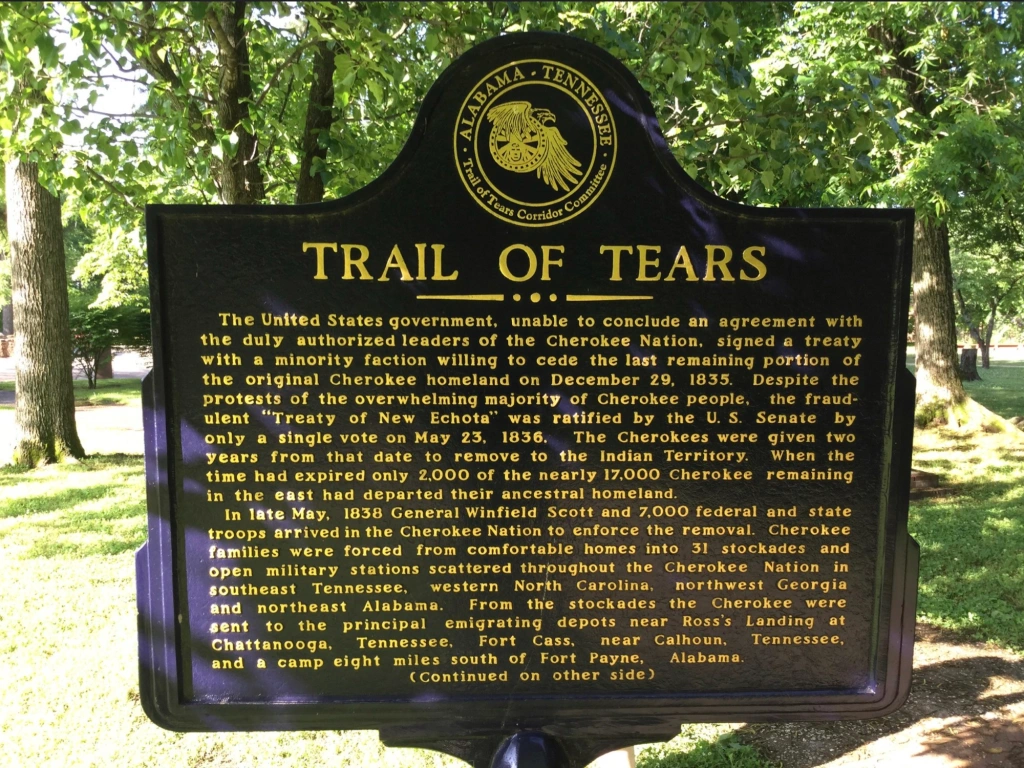

The Cherokee Trail of Tears and legendary chiefs like Geronimo and Sitting Bull are well-known names from a dark chapter of US history on the forced removal of Native Americans. Sometimes removal came more subtly however; arriving at the end of a pen rather than the muzzle of a gun. For the Brothertown Indians, decades of treaties, correspondence, and acts of government tell the story of a less obvious path of forced removal.

Between March 1775, when the first Indians removed to what would become Brothertown in upstate New York, until January of 1834 when the tribe began settling on the east side of Lake Winnebago, the Brothertown Indians had moved seven times.[1] Their last two moves were within Michigan Territory, on land that would later become the state of Wisconsin.

In 1821 and 1822, several New York tribes had treatied with the Menominee and Winnebago for land in the Green Bay area. As the story goes, unable to come up with the full amount of one of their installments, the NY tribes asked the Brotherton if they would join them in their purchase. Because their long-term land deal in White River Indiana had recently fallen through, the tribe agreed. In 1824, six Brotherton, along with their agent, Thomas Dean, went to Green Bay. Through a US government interpreter and agents, they finalized their agreement with the Menominee on September 18th and paid $950 in exchange for a 153k acre tract in the Green Bay area.[2] The treaties were afterwards contested and went through several renegotiations.[3]

After a February 17, 1831 treaty revision, a number of Brothertown families removed to their purchased land.[4] Samuel Stambaugh, US Indian Agent at Green Bay from 1831-’32, reported that, “about 20 Brothertown Indians…came here this fall” and “commenced a settlement at the Little Kaccalin, on the east side of Fox River….”[5] Stambaugh told them they could not settle there but they remained and a second group of about 40 persons arrived in 1832.

A letter from the Brotherton to President Andrew Jackson, dated September 1, 1832, points out the urgency of reaching a final treaty agreement: “…about 40 persons who are unprovided with houses…should be informed where their future is to be that they may erect houses to protect them from the cold of the approaching winter and clear land so that they can raise a crop this next season.”[6]

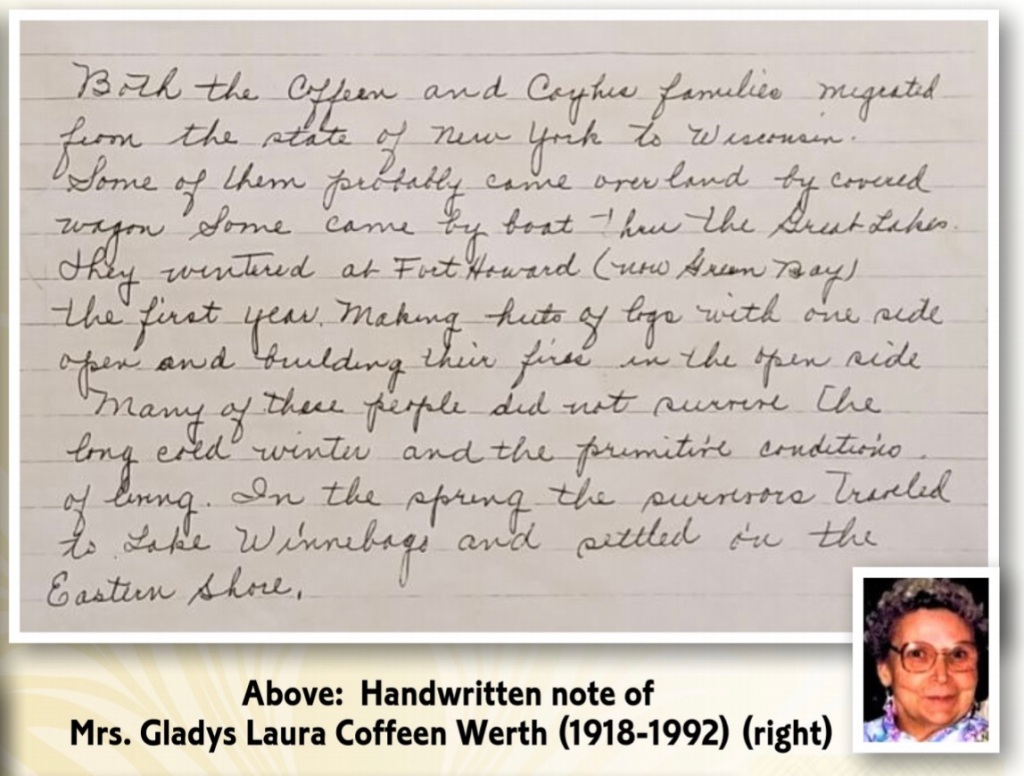

The unsettled treaty soon became not just an inconvenience, but a matter of life and death for those at “Shantetown.”[7] A note handed down to Brotherton Paul Werth from his grandmother, Mrs. Gladys Laura Coffeen Werth, states that, “They [Coffeen & Coyhis families] wintered at Fort Howard (now Green Bay) the first year. Making huts of logs with one side open and building their fires in the open side. Many of these people did not survive the long cold winter, and the primitive conditions of living.”

In an effort to be proactive in avoiding future moves and land troubles, in their 1832 letter to Jackson, the Brotherton also state their acceptance of the proposed changes to their land purchase “…provided the government of the United States, [will] secure the title…by a patent from the government of the United States in fee to the Brothertown Indians…”[8] Owning their land “in fee” would mean they owned the property permanently; just as US citizens held their property. This was different than holding the “Indian title”—which meant the US government held the land, ironically, “in trust” for them. The tribe could live on the land communally but did not have power over it.

The final version of the treaty, dated October 27, 1832 and ratified March 13, 1833, “further secured to the Brothertown Indians the right to have the same partitioned, divided, and held by them separately and severally in fee-simple.”[9] Their original 153,000 acres was reduced to 23,040 and instead of being right off the Fox River, which made it easy to reach, they were moved to a more remote location. However, having been assured they would receive land patents in fee simple, they were willing to make these concessions and move to “Winnebago Lake.”[10]

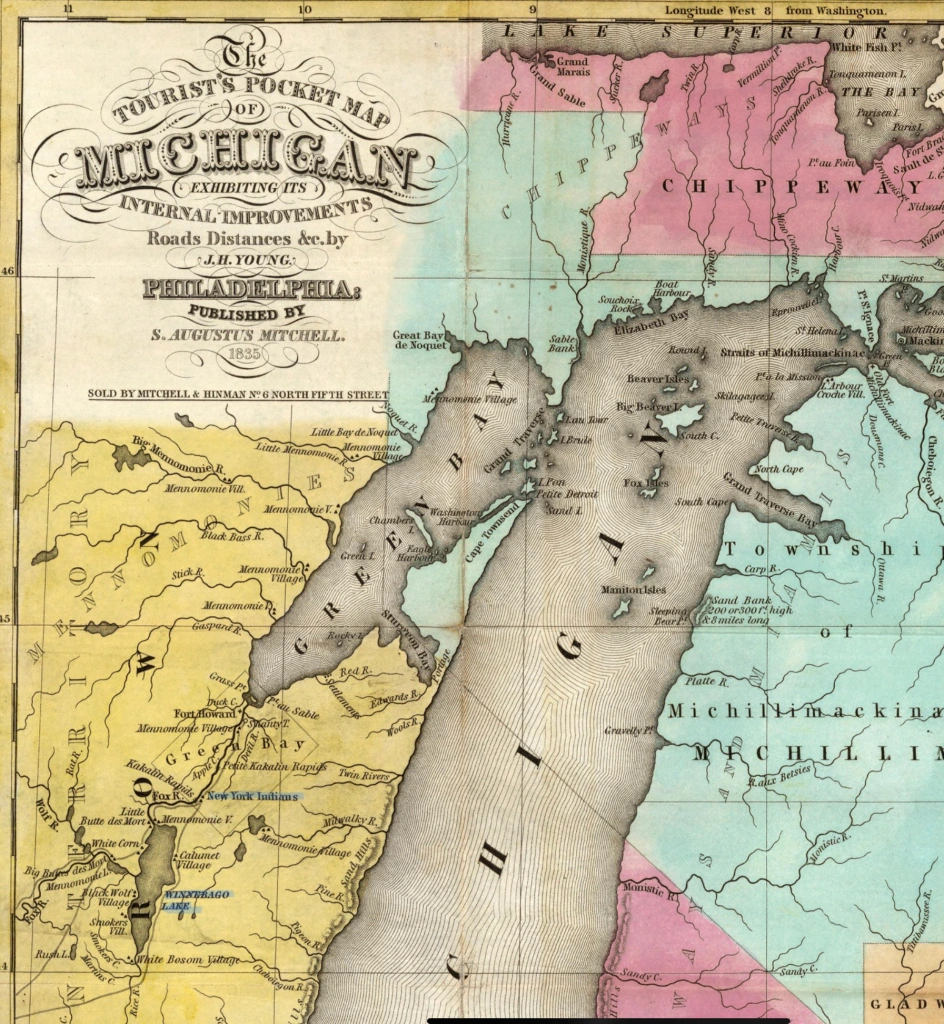

This is a closeup of the top left corner of an 1835 map. 2 areas in the bottom left have been highlighted to show where the “New York Indians” lived in the first half of the 1830’s and then, where they were removed to beginning in 1834.

In January of 1834, ten years after their original 1824 purchase, the first few families were finally allowed to move to what they hoped would be their permanent home on the east side of Lake Winnebago. They cleared the land and built houses. As time passed, more families arrived from the Green Bay settlement and from New York.[11] The 68 Brotherton at the settlement in Green Bay in 1833, turned into 129 by 1835 in their new town of Deansburgh.[12] Still, they did not receive the title to their lands individually in fee-simple as the treaty had specified.

In a letter to Thomas Dean October 26, 1836, the portion of the tribe in Wisconsin wrote requesting that he attend the next session of Congress to “…have this tract of land secured to us, the Brothertown people by the letters pattent from the government of the United States….”[13]

Headman, Thomas Commuck, sensing the futility of their plight, wrote a personal letter to Dean six days later saying, “The plans of the government of the US are laid, and I think that it is useless to continue with the government and we must go over the Mississippi or become citizens here….the Brothertown people…say that they will never leave this tract of land…and that the government has nothing nor ever will, in their opinion, have anything to do with us, the Brothertown people. But I for one, am of a very different opinion—all Indian People are about to be done away with.”[14]

Things were not only tense for Brothertown during this time, but for all of Indian country. While tribes like the Chickasaw had already been forced west in the 1820s, when President Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Policy was signed into law in 1830, more tribes were removed: the Choctaw in 1831, Seminole in 1832, Muscogee Creeks in 1834, the Creeks in 1837, and the Cherokee in 1838.[15]. 1838 was also the beginning of what would eventually be known as the Potawatomi Trail of Death.[16a]

All throughout, Indian land continued to be amassed by the US government. Native lands gobbled up through treaties closer to home in the mid to late 1830s included those belonging to the Menominee (1836); Potawatomi (1836); Sacs and Foxes (1836-1837); and the Winnebago (1837).[16b]

By at least mid-1837, negotiations had begun for another treaty which specified the exchange of all lands belonging to the “New York Indians” for Indian Territory west of the Mississippi. A man working for the removal of the Indians on behalf of the United States, visited the Peacemakers and inhabitants of Brothertown, New York on June 10, 1837.[17] He proposed they send a delegation to view the country and choose a location for the tribe. In a letter to their brothers in Deansburgh, the Peacemakers relayed that none of the tribe there were willing to go to view the land as they had no intention of moving to it. If any of those in Michigan Territory wanted to go, there were no objections. The Peacemakers did, however, object to any form of sale of the lands in Michigan Territory adding that “if we were to sell and go west it would not be 20 years and perhaps half that time before we should be told our title to the land was not good and we must remove further.”[18]

Against the backdrop of the Indian Removal Policy, the insatiable thirst of the US government for Indian land, preparations for the Treaty of Buffalo Creek, and the failure of the US government to adhere to its treaty provision in providing title to their purchased lands in fee simple, it was no longer a matter of if the Brotherton would be removed but when. The only choice remaining to the tribe now was whether that removal would occur by moving further west or, as Commuck had suggested, by becoming US citizens. In other words, by being divested of their land or divested of their tribal sovereignty.

Becoming US citizens would mean not being forced to move again and being able to hand their farms on to their chidren. It would give them the ability to enforce civil laws in their town (backed by state and federal authority) and provide a solution for how to try criminals. Maybe it would even put them on a more equal footing with their white neighbors and lessen some of the prejudicial treatment they received.[19] But, ultimately, becoming US citizens would also mean being stripped of their status as a tribal nation.

On the other hand, moving west meant being always at the mercy of the federal government and its fickle maneuvers. It meant continued poverty, instability, and the loss of life.[20] If there was any hope for a better life for their people, they would need to stay put. With the government’s failure to live up to its treaties, there really was no other viable option. On November 25, 1837, the tribe wrote to Congress, still seeking title to their land but, this time, also adding a request for US citizenship.[21]

Three months after the Second Treaty of Buffalo Creek was signed (which none of the Brotherton were a party to), and faithful to the request of his friends, Thomas Dean visited the city of Washington and there, April 14, 1838, drafted his speech to the US Senate Committee on Public Land. He began by reminding them of the agreements they had previously signed and approved and the validity thereof. He states, “It was from the assurance that their 23040 acres was to be granted to them in fee that they were willing prevailed on to relinquish so large a tract for which they had only acquired the Indian title for so small a tract as to be granted to them on the east side of the said lake.” He eventually winds down his case by saying he hopes and believes Congress will, as given by the Senate’s words in the proviso and resolution, “pass a law directing that a patent be issued to the Brothertown for the township of land.” Knowing their choice between the two options available, and the probable lynchpin of their case for the US, he ends the draft with a one paragraph history of the tribe and their lifestyle adding that “…it is believed they will make useful citizens if they have equal privileges.”[22]

This time, their request was acknowledged and, on March 3, 1839, approved through bill H.R. 1112.[23] The Brotherton finally succeeded in obtaining their land patents in fee simple and remaining in their homes (at least temporarily). After the President of the United States received a report that they had complied with the provisions of the Act of 1839, the status of the Brothertown Indians on the east side of Lake Winnebago changed; they went to sleep November 26, 1839 as Brothertown citizens and awoke the morning of November 27th United States citizens—stripped of the legal right to their tribal status and citizenship.[24] Although in 1924 the Indian Citizenship Act would automatically make all Native Americans US citizens while still retaining their tribal citizenship, that was not the case here; the legal right to their tribal status was removed from the Brothertown Indians in Wisconsin by the stroke of a pen.[25]

On April 15, 1980, the Brothertown Indians filed a letter of intent with the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) letting them know that they would be applying for re-recognition of their tribal status. A tribal narrative was submitted in 1995 followed by an updated and sourced petition in 2008.[26] In 2009, the tribe was notified by the Office of Federal Acknowledgement (OFA) that they had not met all of the federal criteria for tribal nation status so could not be recognized. After further review, they were told, in 2012, that OFA lacked the power to reinstate them; since the tribe had been terminated by an Act of Congress, they could only be restored by another Act of Congress.[27] Now, into their 6th decade of fighting for tribal restoration, the Brothertown Indians are working to introduce Congressional legislation that they hope will restore their government-to-government relationship with the United States.

The path of forced removal of the Brothertown Indians in Wisconsin from the legal right to their tribal status is clearly found in documents and articles involving the tribe throughout the early 1800s. Despite this “paper trail of tears” however, the Brotherton have persisted. 185 years after its dispossession as a tribal nation, the Brothertown Indian Nation of 2024 continues to exercise its tribal sovereignty through its Council and Peacemakers, the creation and celebration of its own national holidays, the repatriation of tribal belongings, its government-to-government relationship with other tribal nations, and the education and engagement of its people who gather regularly for communal and regional events.

Eeyawquittoowauconnuck!

[1]Wisconsin Enquirer; Madison, Wisconsin; Sat, Jun 15, 1839, Page 3; To NY in 1775 &ff, to Stockbridge (1777) during the War; back to NY (1784ish); to one side after BT, NY divided(1796), some to Indiana (1817/’18), many to Green Bay 1831&ff; thence to “Winnebago Lake” in 1834. “Move” here is defined to include a minimum of 3 families.

[2] Indiana Historical Society(IHS); Dean Family Papers, b2f7a; p18-19. ‘Statement of Thomas Dean his work as agent for Brothertown Indians”; City and county of Washington, District of Columbia, January 1832; and IHS, “Treaties”, September 18, 1824 amendment.

[3]Thomas Dean to the Committee on public land of the Senate of the United States; 4-14-1838; Indiana Historical Society, Dean Family Papers, Box 3, folder 2b; pp9-12.

[4] DeLoss Love, Wm; Samson Occom and the Christian Indians of New England, pp321-325.

[5]Wisconsin Historical Collections, Volume XV(1900); p405 & 407. https://content.wisconsinhistory.org/digital/collection/whc/id/7725; accessed 2/13/24.

[6] IHS, Dean Family Papers; b2f7a; pp13-15.

[7] William Dick to Thomas Dean; July 23, 1832; IHS,B2F7b; p4.

[8] Ibid. Note: Italics and bold added.

[9] “The Brothertown Indians”, Chicago Tribune; Chicago, Illinois, December 25, 1877, p2. Note: Bolding added.

[10] BTI letter to Congress 11-25-1837, IHS; Dean Family Papers; B3f5a; p35-38.

[11] Wisconsin Enquirer; Madison, Wisconsin; Sat, Jun 15, 1839, Page 3.

[12] IHS, b2f8, p 4; IHS, b2f9b, pp1-4.

[13] IHS, Dean Family Papers; B3f2a; pp 18-20.

[14] IHS, Dean Family Papers; B3F2a; pp 21-23. Note: Italics and bold added.

[15] https://www.thoughtco.com/the-trail-of-tears-1773597; http://www.seminolenation-indianterritory.org/trailoftears.htm; https://www.nlm.nih.gov/nativevoices/timeline/286.html; https://www.thoughtco.com/the-trail-of-tears-1773597; https://visitcherokeenation.com/culture-and-history.

[16a] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Potawatomi_Trail_of_Death

[16b] Image 552 of U.S. Statutes at Large, Volume 7. Treaties Between the United States and the Indian Tribes (1789-1845); pp519-557. https://www.loc.gov/resource/llsalvol.llsal_007/?sp=552&st=text&r=-0.045,0.123,1.375,1.769,0.

[17]NY Peacemakers letter-“Dear Brothers”; Indiana Historical Society; Dean Family Papers; b3f5a; pp1-2.

[18] Ibid

[19] Wisconsin Enquirer; Madison, Wisconsin; Sat, Jun 15, 1839, Page 3.

[20] Note: At least 9 Brothertown Indians died as a result of the move from NY through Green Bay to Lake Winnebago—see Cutting Marsh diaries at WHS 1832-1837.

[21] BTI letter to Congress 11-25-1837, IHS; Dean Family Papers; B3f5a; pp35-38.

[22] “To the Honorable the Committee on public land of the Senate of the United States”; IHS Box 3 folder 2b pp9-12.

[23]http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=llhb&fileName=025/llhb025.db&recNum=2287; accessed 2/20/24.

[24] https://www.bia.gov/sites/default/files/dup/assets/as-ia/ofa/petition/067_brothe_WI/067_pf.pdf; p 5. Ed. Note: It is important to note that the Brotherton still remained a close-knit community and still self-identified as Native Americans, despite the sting of losing, in the eyes of the US government, the legal right to their tribal citizenship.

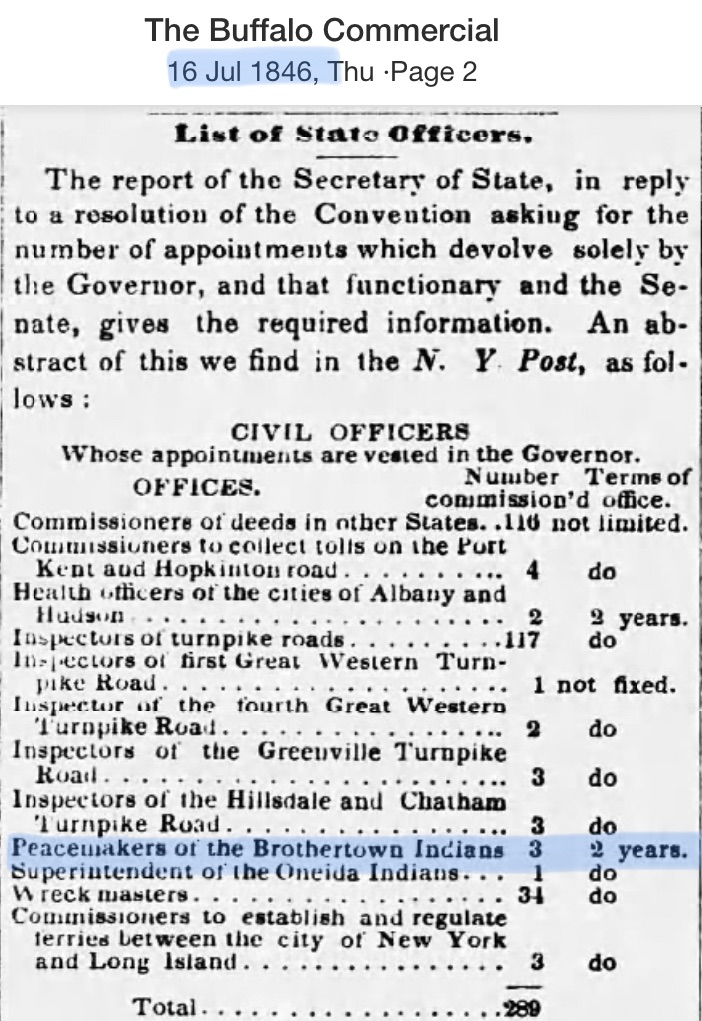

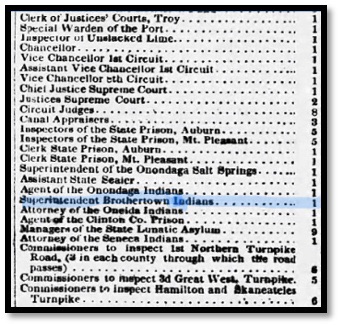

[25] https://www.thoughtco.com/indian-citizenship-act-4690867; The Brothertown tribe in NY was not affected by this decision as Bill 1112 specifically related to the “Brothertown Indians, in the Territory of Wisconsin” (http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=llhb&fileName=025/llhb025.db&recNum=2287). The Peacemakers of the Brothertown Tribe in NY continued to be elected every 3 years as did a Superintendent (See The Buffalo Commercial; Buffalo, New York; Thu, Jul 16, 1846, Page 2). Note: The screenshot of the Buffalo Commercial has been truncated.

[26]Andler, Caroline, email to the author. February 25-28, 2024.

[27] For a somewhat more detailed timeline of recognition-related events see https://brothertowncitizen.wordpress.com/restoration-timeline/

Thank you for shedding light on why we ultimately asked for citizenship. Hearing many members (and many who should know better) say “We asked for citizenship, to hold onto our land” without fully grasping the “why”, is disheartening. Your article helps many finally understand the whole story. We did everything in our power to legally own our land as promised, but we were forced to ask for citizenship when we had no other options. This is a story that every Brothertown member should know, understand, and use. We can no longer limit our historical chronicle to just “asking for citizenship to keep our land,” as we did not ask for citizenship as a mere formality. Our struggle is a factual and central part of our Restoration messaging that must be shared whenever this comes up. We need to be mindful of our audience’s understanding of those “simple words” used in the above telling (That we have all heard) and not assume the listener knows the whole story. We must educate and inform others about the truth and include it in our history packets, brochures, and anything public-facing. Thank you for bringing the truth to all members! Thank you, wottery

LikeLike

Thanks for reading and for your comments!

LikeLike